Playing With “Originals”: On the Importance of Adaptation in Polish Theatre

Playing With “Originals”: On the Importance of Adaptation in Polish Theatre

by Kasia Lech

In the “Najlepszy, najlepsza, najlepsi” (Best, Best, Best) for the 2022/23 season by theatre magazine Teatr – an annual poll in which experts name the best theatre of the season – the overwhelming majority of the shows named are adaptations. By adaptation, I mean diverse works created through one “text” – a novel, a play, a film, a cookbook, a game, and so on – being transformed into a new context. Created by Dorota Kowalkowska and Maciej Podstawny for STUDIO teatrgaleria inWarsaw , Wyspa Jadłonomia (The Jadłonomia Island) was based on Marta Dymek’s series of vegan cookbooks. The production was aimed at audiences aged ten and above, and invited spectators to engage with green activism. At the Jerzy Szaniawski Theatre in Wałbrzych, Agnieszka Wolny-Hamkało and Martyna Majewska adapted the 1976 Brazilian soap opera Niewolnica Isaura (Isaura: Slave Girl), which was itself an adaptation of the 1865 novel by Bernardo Guimarães. The Wałbrzych production interrogated the Polish gaze on the series, which was hugely popular in the 1980s.

De avond is ongemak (The Discomfort of Evening), a Dutch novel by Lucas Rijneveld (formerly Marieke Lucas), was reimagined for stage by Małgorzata Wdowik and Robert Bolesto as Niepokój przychodzi o zmierzchu. Presented by the Wrocław Pantomime Theatre, the production told a story of loss, trauma, and coming-of-age in a hauntingly fairy-tale like scenography by Belarusian Aleksandr Prowaliński. Weronika Murek and Jakub Skrzywanek worked with reportages on a systemic crisis in Polish child psychiatric care and interviews with diverse groups. Their SPARTAKUS: Miłość w czasach zarazy (SPARTACUS: Love in the time of plague) asked important questions about responsibility for the crisis and suicides of children and tried to imagine alternatives to the crisis and contemporary Poland.

Was there something unique about the 2022/23 season that so many adaptations happened? No. There is also nothing wrong with Polish contemporary playwrighting. Thanks to the efforts of Dialog – a monthly magazine publishing new texts for theatre – and events such as Gdynia Drama Award and the National Competition for Staging Contemporary Polish Plays, Polish playwrighting is flourishing. Yet, Polish theatre needs adaptation because the form is deeply ingrained in its (hi)stories, its traditions, modes of practice and aesthetics. Adaptation is embedded in how theatre in Poland relates itself to the world and to itself. Adaptation is a means of a dialogue with the source, the source’s traditions, and Poland and its society. It is through adaptation that Polish theatre, for centuries, has taken a leadership in important socio-political debates.

Marking historic moments

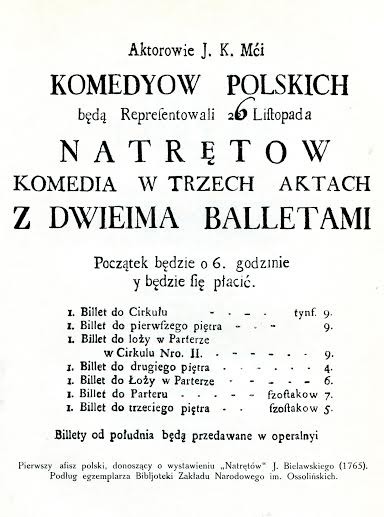

Firstly, some adaptations became a part of Poland’s national heritage through their importance for Polish theatre’s histories, their unique aesthetics, and how they tested various political moments in Poland. The first Polish tragedy – Jan Kochanowski’s Odprawa posłów greckich (The Dismissal of the Greek Envoys) – adapted the plot of Homer’s Iliad. The play was first performed in 1578 at a high aristocracy’s wedding and presented Polish aristocracy in the sixteenth century as a threat to the country’s future. The first-ever premiere at Poland’s National Theatre - Natręci (The Bores) by Józef Bielawski (1765) – was also an adaptation. Bielawski used the plot structure from Molière’s Les Fâcheux (The Bores) to stage the conflict between different visions for Poland and criticize the Polish nobility’s lifestyle and ideology. A century later, as Poland was battling with occupation by Prussia, Russia and Austria – Juliusz Słowacki transferred from Spanish Pedro Calderón de la Barca’s El príncipe constante under the title Książe Niezłomny (The Constant Prince) (1843). This translation-adaptation – considered one of the most important texts in Polish theatre – developed and emphasized the martyrological aspects of Calderón’s drama. Martyrology was at the centre of Polish Romanticism’s idea of regaining freedom for the country. Słowacki’s text also introduced new aesthetics into Polish verse drama.

Considering these historic examples, it seems appropriate that in 2024, an adaptation of Stefan Żeromski’s nineteenth-century novel marks another new turn in Polish theatre. The Modjewska Theatre in Legnica – a public institution in southwestern Poland – has just premiered its first ever production co-funded by audiences who covered half the budget: Dziejów grzechu. Opowiedzianych na nowo (The Story of Sin. Retold again) directed by Daria Kopiec. Crowdfunding is a new turn in Polish public theatre, which always has been funded mainly by national and local governments.

Freedom of Adaptation or Adaptation as Freedom

Between 1795 and 1989, Poland spent 173 years (out of 194) in a situation of bondage. From 1795 until 1918, its territories were taken by Russia, Prussia and Austria; in 1939 Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia attacked Poland starting World War II; and post-war Poland was a part of the Soviet bloc until 1989 when the communist rule ended in Poland. These were times of censorship, that, at the same time, asked for public debates. Some of such discussions were led by playwrights abroad, such as Adam Mickiewicz and later, Witold Gombrowicz or Sławomir Mrożek. However, as Poland’s theatre has been seen throughout its history as an essential platform for political debates, it used adaptations of classical texts to speak to its contemporary moments and escape censorship.

The 1969 version of Calderón’s La vida es sueño (Life is a Dream) by Jarosław Marek Rymkiewicz is an example. Calderón placed the play in Poland as a far-away and fable-like land (and a metaphor for Spain in the seventeenth century), where King Basilio deals with the consequences of imprisoning and raising his son Segismundo in a tower as a way of defying the stars that predicted Segismundo would be a monster. The questions of power and fate resonated with Rymkiewicz, but, at the same time, these questions were very specifically situated in Poland under communist rule. Poland was close and real. In his version of Calderón’s play – Życie jest snem (Life is a Dream) – Rymkiewicz decided to play with this tension between the closeness and “awayness” of Poland. On the one hand, to highlight the foreign roots of the play and move it away from Poland (and away from a censoring eye), Rymkiewicz did not translate Polonia to Polish as Polska, but left it in Spanish. He also “allowed” the characters to “speak” Spanish. The characters use titles like señora, señor, vuestra alteza (Your Highness), and principe. At the same time, he reimagined the characters as actors who suffer from the roles imposed on them by external forces. For example, in Calderón’s Princess Estrella is engaged to Astolfo, Prince of Moscow. Rymkiewicz situates this specifically in Polish context, giving Estrella a distinctive rhythm of verse that creates an effect as if she was crying inside, suggesting her struggle with the idea of marrying a Russian. This spoke to communist Poland’s faith tied with the Soviet Union.

Polish theatre found Rymkiewicz’s version very topical, and in its first year five different directors decided to stage it. The text also became the source for what many critics considered one of the most important works in the post-war Polish theatre: the 1983 Jerzy Jarocki’s production for the Stary Theatre in Kraków. This is even though the initial reviews were cold, which Beata Guczalska interprets as the critics trying to protect Jarocki’s production from the eye of censorship (p. 41). A powerful political context was attached to this production, which premiered in the final days of Martial Law, introduced by the communist government in December 1981. Moreover, Jarocki’s show built on that, commenting on the reality of Martial Law and the Solidarność movement and recalling other theatre productions that imagined the freedom of Poland defying communist rule. For example, in Jarocki’s show the stars from which Basilio was reading the fate of Poland were arranged to look like the sky above Poland on December 13th 1981, when the Martial Law was announced. The production was performed 167 times and remained in the repertoire of the Stary Theatre until the end of the 1990/91 season.

Six months after Jarocki’s show, in January 1984 and also at the Stary Theatre, Andrzej Wajda staged another adaptation that commented on Poland’s 1980s socio-political reality: Sophocles’ Antigone. Wajda imagined Chorus that commented on events to mirror the diversity of voices in Polish society: women and men, technocrats, military, youth, and workers. Antigone was equated with the anti-communism strikers, foretelling the fall of the Soviet rule in Poland and the East of Europe.

In contemporary Poland, adaptations remain a platform for complex socio-political debates. Antonina Grzegorzewska’s 2010 adaptation of Sigrid Undset’s short story Thjödolf as Migrena [Migraine] explores connections between language and the oppression in meat-eating and sexual consumption. Anna Augustynowicz in her 2010 production at the Współczesny Theatre in Szczecin placed the story in a slaughterhouse, emphasizing and interrogating the oppressive structure surrounding human and animal mothers. Three dramaturgs – Agnieszka Jakimiak, Joanna Wichowska, and Goran Injac – worked with Oliver Frljić on an adaptation of Stanisław Wyspiański’s play Klątwa (The Curse, 1899). In a painfully precise manner, the 2017 production by the Powszechny Theatre in Warszawa, asked questions about Poland’s relationship with the Catholic church. It became one of the greatest scandals of Polish theatre’s history. In 2023, Jakub Skrzywanek with the Polski Theatre Underground and the Pantomime Theatre in Wrocław revisited Fjodor Dostojewski’s Crime and Punishment. They attempted to stage Russia’s crimes on Ukraine, and, at the same time, they questioned whether this is at all possible in theatre. The production skilfully played with audiences’ emotions and biases to interrogate Polish gaze on the war. It bitterly reflected on the impossibility of staging war crimes, and simultaneous compulsion, and the necessity to continue to do so.

Adaptation as reimagining and rewriting

What may also become apparent from previous examples is that adaptations have also provided opportunities for directors’ visions, the development of their aesthetics, and their dialogue with Poland’s theatrical traditions. Jerzy Grotowski’s created and practiced his ideas of “total act” – the possibility of experience that goes beyond human life – through his world-famous adaptations of Juliusz Słowacki’s Kordian (1962), Stanisław Wyspiański’s Acropolis (1962), and Książe Niezłomny (The Constant Prince) by Juliusz Słowacki/ Pedro Calderón de la Barca (1965). Krystian Lupa’s adaptation of great European literature – including Thomas Bernhard, Fjodor Dostojewski, and Rainer Maria Rilke – gave him the status of a leading world director and, for some, “the founding father” of Polish contemporary theatre (Gruszczyński).

More contemporary directors work in teams with dramaturgs, together reimagining diverse sources. Jolanta Janiczak and Wiktor Rubin re-read and re-wrote The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov (2016), setting it in contemporary Warszawa. In the production for Powszechny Theatre in Warszawa, Woland and his devil companions watch and interact with Warszawa’s residents using contemporary technology such as drones. Through that, they try to understand what it means to live in a free country. In March 2024, the Center of Inclusive Art / Theater 21 will explore human-animal relations in Siedem historii okrutnych (Seven cruel histories) inspired by Sunaura Taylor’s book Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation (2017). Justyna Wielgus directs, and Justyna Lipko-Konieczna dramaturges the show.

What all these works – whether created by a “master-director” or by a team – is that the source is often fragmented and put in a dialogue with other sources like poetry, philosophical texts, or other plays. Intertextuality has been a core element of Polish approaches to adaptations. And while this article showed many ways in which adaptation functions in Poland’s theatres, much more is left for you to discover. So go and explore!

Works Cited

Gruszczyński, Piotr. Ojcobójcy. Młodsi zdolniejsi w teatrze polskim, Warszawa 2003.

Guczalska, Beata. Jerzy Jarocki – artysta teatru, Kraków, 1999.